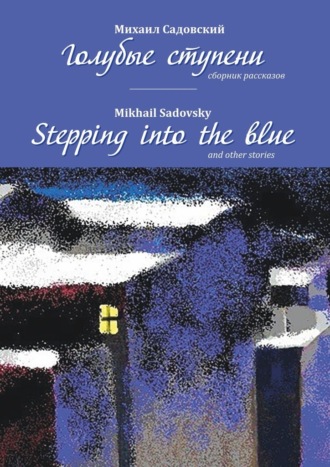

Михаил Садовский

Голубые ступени / Stepping into the blue

Девяносто

Девяносто – это девяносто. Цифра сама по себе всегда пуста, но если твоей бабушке девяносто и она называет тебя «мальчик», а тебе сорок, то есть о чём подумать – сколько уместилось в эту цифру.

– Так, может быть, ты не пойдёшь сегодня в синагогу? Смотри, какая погода.

– Ничего. Погода здесь ни при чём. В моём возрасте нельзя останавливаться. Я ни разу не пропустила, так что сегодня за праздник? С тех пор, как в синагогу стало опасно ходить, я ни разу не пропустила. Когда мужчины стали бояться ходить, так пошла я.

– А ты не боялась?

– Что они мне сделают? Должен же кто-то ходить в синагогу. А то они могли сказать, что раз никто не ходит, так она не нужна, ты что, не понимаешь?!

– Бабушка, как у тебя развито общественное сознание, ого! И что ты просила у Него, чтобы не закрыли синагогу?

– Я никогда ничего не просила. У Него не надо просить ничего.

– Но все просят! И русские в церкви, и татары в мечети, и евреи…

– Нет. Ничего просить не надо. Я рассказываю Ему, что да как, чтобы Он знал правду. А Он уж сам знает, что делать…

– И как ты карабкаешься туда наверх по лестнице…

– Ничего. Понемножку. Но ближе к нему, так Он лучше слышит… я же не кричу… я Ему могу и здесь рассказать… Он всё равно услышит… но, знаешь, я думаю, Ему приятно, что я столько лет хожу в синагогу…

– И всё одно и то же, одно и то же…

– Мальчик, солнце тоже встаёт и садится, а люди родятся и умирают, а деньги приходят и уходят… станешь старше – поймёшь…

– О чём ты, бабушка? Мне сорок!

– Это не тебе сорок – это мне девяносто. Я никогда не просила Его. Бывало так, аж… а фарбренен зол алц верн… дос их хоб гемейнт… ду форштейст, ду форштейст алц… унд их хоб герехнт – дос из а с??…оф…6 Но Он решил, что нет…

– Бобе, майне таере бобе! Их бет дир, леб нох а гундерт ёр!7

– Ты хитрый! Ешефича!.. Ты всё хочешь быть молодым… нет, нет… и хватит об этом… я всё равно не поеду на твоей машине… а если ты мне разменяешь рубль по десять копеек, то я смогу всем дать у входа…

Она собралась потихоньку, в отдельный затрёпанный кошелёчек с кнопочкой посредине сложила разменянный рубль, в карман длинной чёрной юбки засунула другой кошелёк, потолще и побольше размером, натянула старое, но вполне приличное и не засаленное, как обычно у старух, пальто, далеко не закрывавшее юбку, проверила ключи… после этого взяла самодельную можжевеловую очень удобную палку с длинной загнутой ручкой, на которую можно было опереться даже локтем, и вышла из двери.

Девяносто ей исполнилось два месяца назад. Пышно это событие не справляли. Но все соседи откуда-то узнали, и оно почему-то стало событием и для них. Приходили. Звонили в дверь и поздравляли, хотя могли это сделать и во дворе… но приходили… она не то чтобы дружила с ними, с соседями, но когда знала, что кому-то из них плохо, шла и просто помогала, а не спрашивала, надо ли помочь… ещё когда молодая была… она же тут уже не один десяток лет живёт на этом самом месте. У них забирали мужей, она не боялась позвонить в дверь… а забирали обоих родителей, так не боялась пойти покормить оставшихся детей… а когда у неё случилась беда и никто не позвонил в дверь, а на улице, чтобы не обидеть, переходили на другую сторону и не здоровались, она не обижалась… люди есть люди… одни так живут, другие – так… «Сколько мне тогда было? Шестьдесят? Ну, чего можно бояться в шестьдесят? Я же не знала, что проживу до девяноста!» Она не любила вспоминать всё подряд – «валить в кучу», а если вспоминала что-то, то так подробно, будто это происходило сейчас, и она просто пересказывает слепому, чтобы он знал…

Каждый раз она рассказывала Ему историю, и не обязательно о себе, но сегодня день был особенный, и после рассказа она позволила себе спросить: «Готеню, ду бист хот нит фаргесен – их хоб до алейн геблибн? Готеню, их бет дир… нит фаргес он мир… их нор дермон дир…»8 На ступеньках по выходе она раздала приготовленный рубль из кошелёчка: «Зайт гезунт! Зайт гезунт! Зайт гезунт!» – и поковыляла в горку к остановке. Путь ей предстоял неблизкий, но она хорошо знала его и ещё знала, что обязательно доедет до места… троллейбус, метро с пересадкой, автобус – всего часа два в один конец…

У ворот кладбища старуха остановилась перевести дух и оглядеться – ей тут было кого навестить. Она постояла минут пять и отправилась прямо по центральной аллее – теперь совсем рядом, а когда добралась наконец до места, развязала ленточку, вынула её из проушин калитки, вошла внутрь низенькой ограды, уложила две еловые лапы вдоль и выпуклостью вверх, ладонью протёрла фотографию, приблизила к ней лицо, снова вытерла ладонью, потом поцеловала и опустилась на чёрную влажную скамеечку. «Гайнт их хоб до мит дир, Зяме. Ду бист хот нит фаргесен вос фар а тог гант? Нейн, их глейб дир, нейн!..»9

Прохожие, конечно, могли подумать, что тут сидит сумасшедшая старуха и разговаривает сама с собой, что она читает молитву, на самом же деле она просто разговаривала с мужем. «Тогда тоже было пасмурно, и ты, как всегда, торопился, а мне надо было ехать в село – у нас никогда не было времени побыть вместе… и всё же мы, слава Богу, пятьдесят шесть лет прожили вместе, если считать те восемнадцать, что ты сидел, тоже… ну, конечно, считать, если бы мы не ждали, так, может быть, бы и не дожили… с детьми, конечно, не повезло… если бы их было четыре или пять, так ты бы не отказался! Ещё бы! Я знаю! Тебе это очень нравилось… ну, слава Ему, что двоих дал… успели… то ты воевал, то строил… то сидел… а когда ты вернулся, так мне уже сколько было… не будем считать… конечно, мог бы и подождать меня… что ты так поторопился… уходить? Ты всегда торопился! Торопился, торопился! Мне одной сюда ездить тяжело уже… про детей и внуков я тебе говорить не буду – ты и так всё знаешь… а правнуки… ну, эти пишеры… «А дайньк дир, Готеню! Але гезунт!»10

Ребе сказал сегодня, что «возлюби ближнего, как самого себя»! Это относится больше всего к профессии: что сапожнику труднее всего полюбить сапожника, а портному портного, потому что это конкуренция… а что же, наверное, он прав, этот молодой ребе. Он такой умница… конечно, я не сказала ему, что еду к тебе… нельзя же нарушать субботу, но в другой день я не могу – у нас же сегодня юбилей, а не завтра, так Он простит мне, я думаю… но ты мне только скажи, что тебе сегодня приготовить… девяносто – это не так много, если ты можешь сам себе сварить картошку и сходить в магазин за молоком… ну, хорошо, молоко мне приносят… и картошку тоже… и варю я себе очень редко… эта гойка Галка хорошо готовит… но могу я сказать то, что думаю! Что ты молчишь? Ты всегда молчал… когда надо было сказать… а когда надо было промолчать, так тебя вечно за язык тянули… нет… я всё же схожу намочу тряпку – мне не нравится, как ты выглядишь…

Она сходила к крану – воду ещё не успели отключить на зиму – и протёрла ему лицо, как делала это не раз, когда он сваливался с температурой… и каждый раз, как и сейчас, одна и та же мысль приходила ей на ум: «А кто же там обтирал тебя? Ведь не может быть, чтобы ты ни разу не свалился за восемнадцать лет!». Она аккуратно свернула тряпочку, уложила на цоколь позади гранитной плиты… и, распрямившись, шепнула ему прямо в лицо: «Кен сте шен а биселе рюкн… их велт зайн балд… ё… ё…»11

Свет сильно потускнел, и рабочие на мотороллере, которые не раз проезжали мимо, решили сказать Филиппычу, что эта старуха уже который час сидит и сидит в одной позе. Сначала что-то бормотала и качалась, как все евреи, а теперь и вовсе замерла, как статуя. Кто её знает, не померла ли она там, да и холодно… Филиппыч матюкнулся, толкнул толстым пузом стол и, кряхтя, выбрался из-за него. Он шёл по центральной аллее вразвалку и думал, что конец у всех один: всё равно вместе уходят редко, а тому, кто остался, куда тяжелее.

– Вона! – из-за спины указал рабочий, шедший сзади, – сидит не вороqхнется!

Филиппыч остановился возле ограды и кашлянул. Старуха даже не шевельнулась.

– Гражданка! – произнёс негромко Филиппыч, но не получил ответа. – Гражданочка! Территория закрывается для посещения… может, вам помочь? – поинтересовался он, изображая участие в голосе. Старуха медленно повернула к нему тёмное лицо и попыталась встать, опираясь на свою палку, но у неё ничего не получилось. – Помоги, – кивнул Филиппыч назад, и рабочий в телогрейке выдвинулся из-за спины.

– Да я в цементе весь. Не успел, – оправдался он.

Тогда толстый Филиппыч сам, с трудом сгибаясь, наклонился и попытался взять старуху под локоть. Она приподнялась и снова опустилась на скамейку.

– Ну вот! – огорчился он по-настоящему не столько немощи старухи, сколько неожиданно выпавшим хлопотам. – Что ж вы одна-то… да в субботу…

– Ничего! – откликнулась старуха. – Я встану. Я дойду… я одна хотела, потому что… – она замялась, стоит ли говорить, и Филиппыч прервал её:

– В вашем-то возрасте!

– В моём возрасте уже всё можно! И одной по ночам гулять, и в субботу! – неожиданно резко встрепенулась старуха и сделала первый шаг.

– Во даёт! – хохотнул рабочий. – Ну и бабуля! Сколько ж вам стукнуло?

– Девяносто, – ответила она, и все замолчали.

– Сколько? – переспросил Филиппыч.

– Не веришь? – она помолчала. – Мы сегодня ровно семьдесят лет как вместе.

– Как вместе? – удивился Филиппыч и оглянулся на цифры на камне.

– А ты не считай, не считай… эти-то годы идут один за два… так ещё больше получится.

Она почувствовала, что ноги отекли, и вправду вряд ли она сама теперь доберётся до дома, но не ощутила не только никакого страха, но и волнения. Мелькнула, правда, мысль, что дома будут сходить с ума, но поскольку такое случалось уже не однажды, она махнула рукой. Всё равно всё сделала правильно. Они так мало в жизни бывали вместе, что и Зяма наверняка с ней согласен.

– Подгони треногого, – распорядился Филиппыч, и рабочий быстро засеменил обратно по аллее. Вскоре он вернулся на тарахтящем мотороллере, в кузов которого была постелена свежая рогожа.

– Ну, бабушка, садись! – хохотнул рабочий, и они вдвоём с Филиппычем усадили старуху в кузов через низенький бортик.

– К конторе! – распорядился Филиппыч и последовал за ними.

Старуха так и дожидалась, сидя на рогоже, пока он подойдёт и снова поможет ей выбраться на землю. Потом они долго решали, что делать, и она наотрез отказалась ехать на такси, а только просила проводить её до автобуса. После долгих уговоров она согласилась, что Филиппыч довезёт её до троллейбуса – это ему по дороге, а там уж она сама.

– Внук всё записать за мной мою жизнь хочет, – рассказывала она, пока ехали, – а я ему говорю, что толку нет – все мы одинаково жили, ничего особенного, а то, что мне довелось больше других на свете остаться, так это ещё неизвестно – повезло ли.

– Да! – вздохнул Филиппыч и оглянулся. – А вам больше семидесяти не дашь. Не обманываете?

– Зачем? – удивилась старуха. – Ты представь только – я ж ещё при Александре родилась, в черте оседлости!

– А это что такое?

– Что такое? А за ёр аф мир! Что такое? Черта для евреев была.

– Какая?

– Где жить – где не жить!

– Граница, что ли?

– Видно, правда, надо соглашаться мне…

– Чего?

– Да рассказывать! Если такие молодые люди ничего не знают… ты хоть учился где?

– Бауманский закончил, – похвалился Филиппыч.

– Это что же такое?

– Инженером был!

– Инженер – заведует кладбищем!

– Гелт, – просто ответил Филиппыч.

– Ты что, разве а ид? – удивилась старуха.

– Я нормальный. Что, одни евреи умные?! – обиделся Филиппыч. – Неужели всё помните?

Старуха долго не отвечала, так что водитель уже стал беспокоиться и оглянулся назад через плечо.

– Я такое помню, что лучше забыть, – тихо сказала она. – Раньше за это сажали. Теперь всё равно не напечатают. Зачем ему трепать нервы? Пусть это уйдёт со мной. Он же не виноват, что я его бабка…

– Знаете что? Я вас довезу до дома. Куда вы в такую темень и с такими ногами…

– Нет, – возразила старуха. – Я должна сама домой вернуться. Так надо. Мне надо и Ему…

Филиппыч не понял, кому «ему», но уточнять не стал. Он высадил её на остановке, помог забраться в троллейбус и ещё долго стоял, переваривая произошедшее с ним и завидуя неизвестному внуку. У него-то не было стариков – одни лежали в земле далеко на западе, другие далеко на востоке, и никто не мог даже сказать ему, где их могилы.

Ninety

[Devianosto]

Ninety is ninety. The number all by itself may always have an empty ring about it, but when your grandmother is ninety and she calls you «little boy» and you’re forty, well, that’s something to think about. Just think of how much is wrapped up in that one little number!

«So, maybe you won’t be going to the synagogue today? Look at the weather!»

«That’s no matter. Why should I care about the weather? At my age I can’t afford to stop going. I haven’t missed once yet, so why should I take a holiday today? Ever since it became dangerous to go to the synagogue, I haven’t missed a single time! Even when the men were afraid to go, I still went!»

«And you weren’t afraid?»

«What would they do to me? Somebody has to go to the synagogue. Else they could say that now nobody goes there it isn’t needed any more. Something about that you don’t understand?»

«Grandma, what an advanced social consciousness you have. Wow! So, you asked Him not to let them close the synagogue?»

«I’ve never asked anything. I certainly don’t have to ask Him anything.»

«But everybody asks Him! The Russians in their churches, the Tatars in their mosques, and the Jews…»

«No. There’s nothing that needs asking for. I tell Him what the situation is so that He’ll know the truth. And He Himself knows what to do.»

«And how do you plan to get yourself up those stairs?»

«That’s no matter. Little by little. But the closer I get to Him, the better He’ll hear me. I don’t exactly shout, you know. I could even tell it all to Him right here, He’d still hear me. But I think He’s pleased that I’ve been going to the synagogue all these years.»

«Everything’s all the same, it’s all the same.»

«Little one, the sun too rises and sets, and people are born and die, and money comes and goes. When you get older, you’ll understand.»

«What do you mean, Grandma? I’m already forty!»

«It’s not that you’re forty, it’s that I’m ninety. I never have asked Him. It happened once that – a verbrennen soll alts wern… das ich hab gemeint… du verstehst, du verstehst alts – und ich hab gerechnet – das ist ein sof (I should let it all all burn up… that’s what I thought… you understand, you understand it all, and I decided then that this was the end). But He decided otherwise.»

«Bobei, meine teure Bobei! Ich bet dir, leb noch ein hundert jahr! (Grandma, my dear Grandma! I beg you, live a hundred years more!)»

«Oh, you’re tricky! Yeshefitcha (A real sweetikins)! You still want to be young! No, no, enough about that. I still won’t go in your car. But if you change a rouble for me and give me ten-kopeck pieces, I can give out some money to everyone as they walk out.»

Little by little she got herself ready. She deposited the change from the rouble into a ragged little purse with a button in the middle. Another purse, a little larger and fatter, was dropped into the pocket of a long black skirt. Then she pulled on an old but still quite respectable overcoat which barely covered her skirt (though it wasn’t a dirty-looking coat like the ones most women her age wore). After checking her keys, she took out a home-made juniper walking-stick, a very nice one with a long curved handle, on which she could even support herself with one elbow, and set foot out the door.

She had turned ninety two months ago. There was no fancy celebration. But all the neighbors somehow found out about it and came round. They rang the doorbell and offered their congratulations, even though they could have done this on the street. But still they came. She hadn’t really been close friends with them, the neighbors, but whenever she learned that someone was ill, she invariably went over and simply extended her help without even asking whether the help was required. She had done this even as a young woman. She had been living in this same spot for several decades already.

She wasn’t afraid to ring anyone’s bell. Their husbands had all been taken away by the secret police. And where both parents had been taken, she wasn’t afraid to go and feed the children that had been left behind. And when disaster befell her, and nobody rang the doorbell, and when people saw her on the street, and would simply cross to the other side and not say hello so as not to make trouble,12 she didn’t take offense. People were people, after all. Some lived one way, some another.

«How old was I then? Sixty? Well, what is there to be afraid of at sixty? I didn’t know then I’d be alive at ninety!»

She didn’t like remembering everything all at once, which she considered tanatamount to «throwing everything together in a heap», but if she happened to recall something, she would remember it in such detail as though it had occurred just a few moments ago and she were simply explaining the scene to a blind person so that he would know what was going on.

And then at every opportunity she would tell Him the story too, not necessarily about herself, but today was special, and after her account she allowed herself to ask: «Gotteniu, du bist hat nicht vergessen – ich hab doch allein geblieben? Gotteniu, ich bet dir, nicht vergess uben mir. Ich nur dermahn dir. (Lord, you haven’t forgotten about me – am I the only one left here? Lord, I beg you, don’t forget about me. Just reminding you!)»

On the steps of the synagogue near the exit she handed out the ten-kopeck pieces from her purse, saying «Seit gesund! Seit gesund! (Be healthy! Be healthy!)» and shuffled up the hill to the bus stop. She had a long journey ahead of her, but she knew the way quite well, and, what’s more, she knew she would get there for certain. First a trolleybus ride, then it was on to the subway with one transfer, and finally another bus ride – about two hours altogether one-way.

At the gates to the cemetery she stopped to catch her breath and look about her. There was someone she needed to visit here. She stood still for five minutes or so and then headed down the central allée – she was getting close now. At the familiar little gate she undid the cord fastener and entered the low-fenced enclosure. After placing two fir boughs on the grave, bushy side up, she wiped the enamelled photograph on the headstone with the palm of her hand, put her face up close to it, wiped it once again, then kissed it and took her seat once more on the damp black bench.

«Khaint ich hab do mit dir, Ziama. Du bist hat nicht vorgessen was vor ein Tag khaint? Nein, ich gleib dir, nein! (Today I’m here with you, Ziama. You haven’t forgotten what day it is today. No, I’m sure you haven’t!)»

Passers-by naturally might have surmised that here was just a crazy old woman talking to herself. Somebody might have thought she was saying a prayer. In fact, she was simply talking with her husband.

«It was a cloudy day back then too, and you were in a hurry, as always, and I had to get to the village. We never had time to be together back then. Still, thank God, we lived fifty-six years together, if you count the eighteen you spent in prison. But of course they count! If we hadn’t been waiting for each other all those years, we might not have survived.

«It didn’t work out with the children, because of that. If we had had four or five, you wouldn’t have minded! I should say not! I know you! You were happy about that. But thank God He gave us two. We pulled through! You were either fighting or building, or in prison. And when you came back, I was oh so many years older – we won’t even count them.

«Of course it would have been nice if you’d waited for me. What were you in such a hurry for – to leave? You were always in a hurry! Hurry, hurry, hurry!

«It’s getting difficult for me to get here on my own. I won’t tell you about the children and grandchildren – you know everything anyway. But the great-grandchildren – well, those pishery (little scribes) – Ach, danke dir, Gotteniu! Alle gesund! (Oh, thank you God! All are healthy!)

«The rabbi said today that we should «love our neighbor as ourselves» – and that this applies most of all to people of the same profession. Like for a cobbler it’s hardest of all to love another cobbler, or a tailor to love a tailor – because of the competition.

«Well, what d’you know, he’s probably right, that young rabbi. He’s such a clever fellow. Of course, I didn’t tell him I was coming to see you. One shouldn’t break the sabbath, but I couldn’t do it any other day. It’s our anniversary today, not tomorrow, so I think He will forgive me.

«But you just tell me what I should cook for you today. Ninety’s not all that much when you can boil your own potatoes and go to the store for milk. Well, okay, they bring milk to me – potatoes too, and I don’t boil them for myself very often. That Gentile, Galka, cooks pretty good. But I can say what I think!…

«What are you so quiet for? You were always quiet – when you should have talked. And when you should have been silent, you would keep on wagging your tongue without stopping.

«No, I’d better go moisten my cloth – I don’t like the way you look.»

She headed over to the tap – they hadn’t yet cut off the water for the winter – and wiped the face in the photograph, just as she had wiped his face so many times whenever he came down with a temperature. And each time she did this, just like now, the same thought would come to mind: «And who wiped your face while you were in prison? You can’t tell me you didn’t come down with a temperature the whole eighteen years!»

She neatly folded the cloth, placed it on the pediment behind the granite headstone, then straightened up and whispered directly to his face: «Konnst schon ein bissel rucken – ich welt sein bald – ja, ja! (You can start moving over, I won’t be long now – yes, yes!)»

The light had already dimmed quite a bit, and the workers who had passed by her quite a few times in their mini-truck decided they ought to tell Filippovich13 that this old woman had been sitting a long time there without moving. At first she had been chattering away and swaying back and forth the way all Jews did, but now she was sitting there stock still, like a statue. Who knows whether she might have died right then and there – it was pretty cold.

Filippovich let out an oath, pushed the table away with his bulging belly, and got up with a groan. As he ambled along the central allée he thought: everybody dies the same death. Still, it was rare for people to go together. It was always a lot harder for the one left behind.

«There she is!» whispered a voice from behind his back. The worker who had been trailing him pointed. «She just sits herself there and don’t budge.» Filippovich paused by the low fence and coughed. The old woman wasn’t even moving a muscle.

«Hey, lady!» Filippovich called out softly, but with no response. «Hey, lady! The grounds are closing. Do you need help?» He was starting to get involved – you could hear it in his voice.

The old woman slowly turned her dark face toward him and tried to get up, leaning on her walking-stick, but she couldn’t move.

«Give us a hand here!» Filippovich gestured to the man behind him, and the worker, wearing a warm jacket, stepped out from behind his back.

«I’m all stuck here. Can’t do it!» he explained. Then the rotund Filippovich, who had a hard time bending over himself, leant forward and tried to take hold of the old woman’s elbow. She managed to get up, only to drop back to the bench.

«Hoo, boy!» By this time he was really upset, not so much because of the elderly woman’s infirmity as the unexpected challenges that had come his way. «How come you’re all alone here, and on the Sabbath yet?»

«No matter,» came the reply. «I’ll get up. I’ll get there. I wanted to do it on my own, ’cause…» She was wondering whether it was worth the effort to continue speaking, when Filippovich interrupted her:

«And at your age!»

«At my age I can do everything! I can go for a walk alone at night, even on the Sabbath!» Suddenly she gave a start and took a first step.

«Aha, it’s comin’!» the worker chortled. «Well, now, granny! How many years you got under your belt?»

«Ninety,» she answered, to the amazement of all.

«How many?» Filippovich echoed.

«You don’t believe me?» After a pause, she added: «It’s exactly seventy years today that we’ve been… like together.»

«What do you mean, ’like together’?» Filippovich marvelled, looking at the dates on the headstone.

«You don’t know how to count! Can’t count! Those years that went by – every one of them counted as two. So they add up to many more!»

While she felt a swelling in her legs, and wondered whether, indeed, she would make it home now, she was nevertheless completely free of not only fear but even concern. True, the thought did cross her mind that once at home she might go crazy, but since that had happened a number a times already, she dismissed it with a wave of her hand. In any case, she had done everything right. They had been so little together in life that Ziama was probably in full agreement with her.

«Bring the three-wheeler, on the double!» Filippovich barked, and the worker quickly set off back down the allée. He presently returned with a rattling three-wheeled mini-truck sporting a fresh mat on the seat of the cab.

«Okay, granny, get in!» the worker chortled, and he and Filippovich lifted the old woman over the low running-board and sat her down on the seat of the cab.

«Head for the office!» Filippovich commanded as he started to follow them. Upon reaching the office the woman waited until he could catch up with them and help her out.

It took them quite a while to decide what to do next. She flatly refused to take a taxi, asking only that they accompany her to the bus stop. After extensive negotiations she finally agreed that Filippovich could take her as far as the trolleybus near her home, as it was on his way, but after that she would be on her own.

«My grandson wants to write the story of my life,» she told him as they drove. «I tell him there’s no point: we all lived the same kind of life, nothing special, and the fact that I’ve managed to stick around longer than others in this world, well, it still remains to be seen whether that’s an advantage.»

«Mm-hm!» sighed Filippovich, and took a good look at her. «You don’t look a day over seventy! You’re sure you’re not kidding me?»

«What for?» the old woman asked in surprise. «Just think: I was born when Alexander III was on the throne – I was born in the residency perimeter.»

«And what might that be?»

«What was that? A za jahr af mir! (I should have lived like that!) What was that, indeed? A perimeter for Jews.»

«What kind of perimeter?»

«Designating where we could live, where we couldn’t!»

«Some kind of border?»

«It’s obvious, isn’t it – you have to agree I’ve got to…»

«Got to do what?»

«Tell my story, of course! Seeing youngsters like you don’t know anything! Where did you go to school?»

«I graduated from the Bauman,»14 Filippovich boasted.

«What’s that supposed to mean?»

«I was an engineer!»

«An engineer, and here you’re looking after a cemetery?!»

«Gelt (Money),» was Filippovich’s only answer.

«Maybe you’re Jewish?» queried the old woman in amazement.

«No, I’m just a regular guy. You think Jews are the only smart people?» Filippovich took offense. «Don’t you remember it all?»

The old woman didn’t answer for such a long time that the driver was already starting to get concerned and stole a glance over his shoulder.

«The things I remember – well, they’re better to forget,» she said quietly. «Back then I could have been sent to jail just for talking about them. Even now they still won’t publish my memoirs. Why get my grandson all worked up about it? Better they go to the grave with me. He’s not to blame that I’m his grandmother!»

«Know something? I’m going to drive you right home! Where are you headed? It’s dark out, and with those legs of yours?»

«No,» the old woman protested. «I ought to get home on my own. That’s the way it should be. Besides, I owe it to him.»

Filippovich didn’t understand who the «him» referred to, but he wasn’t about to ask for clarification. He let her off at the stop, helped her on to the trolleybus, and then spent a long time just standing there, reflecting on what had happened and envying a grandson he had never met. There weren’t any elderly relatives in his life. They were all dead and buried – either in battlefields far away on the western front, or in the Siberian labor-camps far to the east, and nobody could even tell him where to find their graves.