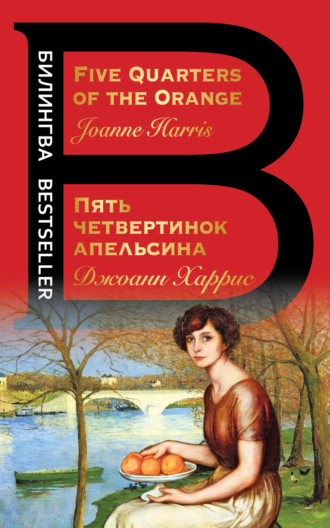

Джоанн Харрис

Five Quarters of the Orange / Пять четвертинок апельсина

“I remember something,” I said at last.

He explained then, patiently. A language of inverted syllables, reversed words, nonsense prefixes and suffixes. Ini tnawini inoti plainexini. I want to explain. Minini toni nierus niohwni inoti. I’m not sure who to.

Strangely enough Cassis seemed uninterested by my mother’s secret writings. His gaze lingered over the recipes. The rest was dead. The recipes were something he could understand, touch, taste. I could feel his discomfort at standing too close to me, as if my similarity to her might infect him too.

“If my son could only see all these recipes-” he said in a low voice.

“Don’t tell him,” I said sharply.

I was beginning to know Yannick. The less he learned about us, the better.

Cassis shrugged.

“Of course not. I promise.”

And I believed him. It goes to show that I’m not as like my mother as he thought. I trusted him, God help me, and for a while it seemed as if he’d kept his promise. Yannick and Laure kept their distance, Mamie Framboise vanished from view and summer rolled into autumn, dragging a soft train of dead leaves.

6

Yannick says he saw Old Mother today.

He came running back from the river half wild with excitement and babbling. He’d forgotten his fish on the verge in his haste, amp; I snapped at him for wasting time. He looked at me with that sad helplessness in his eyes, amp; I thought he was going to say something, but he didn’t. I suppose he feels ashamed. I feel hard inside, frozen. I want to say something, but I’m not sure what it is. Bad luck to see Old Mother, everyone says, but we’ve had enough of that already. Perhaps that’s why I am what I am.

I took my time over Mother’s album. Part of it was fear. Of what I might find out, perhaps. Of what I might be forced to remember. Part of it was that the narrative was confused, the order of events deliberately and expertly shuffled, like a clever card trick. I barely remembered the day of which she had spoken, though I dreamed of it later. The handwriting, though neat, was obsessively small, giving me terrible headaches if I studied it for too long. In this too I am like her. I remember her headaches quite clearly, so often preceded by what Cassis used to refer to as her “turns.” They had worsened when I was born, he told me. He was the only one of us old enough to remember her before.

Below a recipe for mulled cider, she writes:

I can remember what it was like. To be in the light. To be whole. It was like that for a time, before C. was born. I try to remember how it was to be so young. If only we’d stayed away, I tell myself. Never come back to Les Laveuses. Y. tries to help. But there’s no love in it any more. He’s afraid of me now, afraid of what I might do. To him. To the children. There’s no sweetness in suffering, whatever people might think It eats away everything in the end Y. stays for the sake of the children. I should be grateful. He could leave, amp; no one would think the worse of him for it. After all, he was born here.

Never one to give in to her complaints, she bore the pain for as long as she could before retiring to her darkened room while we padded silently, like wary cats, outside. Every six months or so she would suffer a really serious attack, which would leave her prostrate for days. Once, when I was very young, she collapsed on the way back from the well, crumpling forward over her bucket, a wash of liquid staining the dry path in front of her, her straw hat slipping sideways to show her open mouth, her staring eyes. I was in the kitchen garden gathering herbs, alone. My first thought was that she was dead. Her silence, the black hole of her mouth against the taut yellow skin of her face, her eyes like ball bearings. I put down my basket very slowly and walked toward her.

The path seemed oddly warped beneath my feet, as if I was wearing someone else’s glasses, and I stumbled a little. My mother was lying on her side. One leg was splayed out, the dark skirt hiked up a little to show boot and stocking. Her mouth gaped hungrily. I felt very calm.

She’s dead, I told myself. The rush of feeling that came in the wake of the thought was so intense that for a moment I was unable to identify it. A bright comet’s tail of sensation, prickling at my armpits and flipping my stomach like a pancake. Terror, grief, confusion… I looked for them inside myself and found no trace of them. Instead, a burst of poison fireworks that filled my head with light. I looked flatly at my mother’s corpse and felt relief, hope and an ugly, primitive joy.

This sweetness…

I feel hard inside, frozen.

I know, I know. I can’t expect you to understand how I felt. It sounds grotesque to me too, remembering how it was, wondering whether this is not another false memory… Of course, it might have been shock. People experience strange things under the effects of shock. Even children. Especially children, the prim, secret savages we were. Locked in our mad world between the Lookout Post and the river, with the Standing Stones keeping watch over our covert rituals… But it was joy I felt all the same.

I stood beside her. The dead eyes stared at me, unblinking. I wondered whether I ought to close them. There was something disturbing about their round, fishy gaze that reminded me of Old Mother, the day I finally nailed her up. A thread of drool glistened at her lips. I moved a little closer…

Her hand shot out and grabbed me by the ankle. Not dead, no; but waiting, her eyes bright with mean intelligence. Her mouth worked painfully, enunciating every word with glassy precision. I closed my eyes to stop myself from screaming.

“Listen. Get my stick.” Her voice was grating, metallic. “Get it. Kitchen. Quickly.”

I stared at her, her hand still clutching my bare ankle.

“Felt it coming this morning,” she said tonelessly. “Knew it was going to be a big one. Only saw half the clock. Smelt oranges. Get the stick. Help me.”

“I thought you were going to die.” My voice sounded eerily like hers, clear and hard. “I thought you were dead.”

One side of her mouth hitched, and she made a low yarking sound, which I eventually recognized as laughter. I ran to the kitchen with that sound in my ears, found the stick, a heavy piece of twisted hawthorn that she used to reach the higher branches of the fruit trees, and brought it to her. She was already on her knees, pushing against the ground with her hands. From time to time she shook her head with a sharp, impatient gesture, as if plagued by wasps.

“Good.” Her voice was thick, like a mouthful of mud. “Now leave me. Tell your father. I’m going… to… my room.” Then, jerking herself savagely to her feet with the stick, swaying, keeping upright with a simple effort of will: “I said, go away!”

And she struck at me clumsily with one clawing hand, almost losing balance, stubbing at the path with her stick. I ran then, turning back only when I was well out of her range, ducking down behind a stand of red currants to watch her staggering toward the house, dragging her feet in great loops in the dirt behind her.

It was the first time I became truly aware of my mother’s affliction. My father explained it to us later, the business with the clock and the oranges, while she lay in darkness. We understood little of what he told us. Our mother had bad spells, he said patiently, headaches that were so terrible that sometimes she didn’t even know what she was doing. Had we ever had sunstroke? Felt that woozy, unreal feeling, imagined that objects were closer than they were, sounds louder? We looked at him, uncomprehending. Only Cassis, nine then to my four, seemed to understand.

“She does things,” said my father. “Things she doesn’t really remember afterward. Because of the bad spells.”

We stared at him solemnly. Bad spells.

My youthful mind associated the phrase with stories of witches. The gingerbread house. The Seven Swans. I imagined my mother lying on her bed in the dark, eyes open, strange words sliding between her lips like eels. I imagined her looking through the walls and seeing me, seeing right inside me and rocking with that dreadful, yarking laughter… Sometimes Father slept on the kitchen chair when Mother had her bad spells. And one morning we had got up to find him bathing his forehead in the kitchen sink, and the water full of blood… An accident, he told us then. A stupid accident. But I remember seeing blood, glossy on the clean terra-cotta tiles. A length of stove wood had been left on the table. There was blood on that too.

“She wouldn’t hurt us, would she, Papa?”

He looked at me for a moment. A second’s hesitation, maybe two. And in his eyes a look of calculation, as if deciding how much to tell.

Then he smiled. “Of course not, sweetheart.” What a question, his smile said.

“She wouldn’t ever hurt you.”

And he folded me into his arms and I smelled tobacco and moths and the biscuity smell of old sweat. But I never forgot that hesitation, that measuring look. For a second he had considered it. Turned it over in his mind, wondering how much to tell us. Perhaps he’d thought that he had time, plenty of time to explain to us when we were older.

Later that night I heard sounds from my parents’ room; shouting, breaking glass. I got up early to find that my father had slept all night in the kitchen. My mother got up late but cheery-as cheery as she ever was-singing to herself in a low tuneless voice as she stirred green tomatoes into her round copper jamming pan, slipping me a handful of yellow gages from her apron pocket. Shyly, I asked her if she felt any better. She looked at me without comprehension, her face white and blank as a clean plate. I sneaked into her room later and found my father taping waxed paper over a broken windowpane. There was glass on the floor from the window and the face of the mantel clock, now lying face-down on the boards. A reddish smear had dried against the wallpaper just above the bedstead, and my eyes sought it with a kind of fascination. I could see the five commas of her fingertips where they had stabbed at the paper, and the blot that was her palm. When I looked again a few hours later, the wall had been scrubbed clean and the room was tidy again. Neither of my parents mentioned the incident, both behaving as if nothing untoward had happened. But after that, my father kept our bedroom door locked and our windows bolted at night, almost as if he were afraid of something breaking in.

7

When my father died I felt little true grief. When I looked for sorrow I found only a hard place inside myself, like a stone in a fruit. I tried to tell myself that I would never see his face again, but by that time I had almost forgotten it as it was. Instead he had become a kind of icon, rolling eyes like a plaster saint’s, his uniform buttons gleaming mellowly. I tried to imagine him lying dead on the battlefield, lying broken in some mass grave, exploded by the mine that blew up in his face… I imagined horrors, but they were unreal to me as nightmares. Cassis took it worst. He ran away for two days after we got the news, finally returning exhausted, hungry and covered in mosquito bites. He’d been sleeping out on the other side of the Loire, where the woods tail off into marshland. I think he’d had some mad idea of joining the army, but had got lost instead, going round in circles for hours until he’d found the Loire again. He tried to bluff it out, to pretend he’d had adventures, but for once I didn’t believe him.

After that he took to fighting other boys, and often came home with torn clothes and blood under his fingernails. He spent hours in the woods alone. He never cried for Father, and took pride in that, even swearing at Philippe Hourias when he once tried to offer comfort. Reinette, on the other hand, seemed to enjoy the attention Father’s death brought her. People called round with presents, or patted her head if they met her in the village. In the café the matter of our future-and our mother’s-was discussed in low, earnest voices. My sister learned to make her eyes brim at will, and cultivated a brave, orphaned smile that earned her gifts of sweets and the reputation of being the sensitive one in the family.

My mother never spoke of him after his death. It was as if Father had never lived with us at all. The farm went on without him, if anything with even greater efficiency than before. We dug up the rows of Jerusalem artichokes, which only he had liked, and replaced them with asparagus and purple broccoli, which swayed and whispered in the wind. I began to have bad dreams in which I was lying underground, rotting, overwhelmed by the stench of my own decay. I drowned in the Loire, feeling the ooze of the riverbed crawl over my dead flesh, and when I reached out for help I felt hundreds of other bodies there with me, rocking gently with the undercurrent, crammed shoulder to shoulder against one another, some whole, some in pieces, faceless, grinning brokenly from dislocated jaws and rolling dead eyes in garish welcome… I awoke from these dreams sweating and screaming, but Mother never came. Instead Cassis and Reine came to me, impatient and kind by turns. Sometimes they pinched and threatened me in low, exasperated voices. Sometimes they took me in their arms and rocked me back to sleep. Sometimes Cassis would tell stories and Reine-Claude and I would both listen, eyes wide in the moonlight; stories of giants and witches and man-eating roses and mountains and dragons masquerading as men… Oh, Cassis was a fine storyteller in those days, and though he was sometimes unkind and often made fun of my night terrors, it is the stories I remember most now, and his eyes shining.

8

With Father gone, we grew to know Mother’s bad spells almost as well as he had. As they began she would speak with a certain vagueness, and she would suffer tension around the temples, which she would betray by impatient little pecking movements of the head. Sometimes she would reach for something-a spoon, a knife-and miss, slapping her hand repeatedly against the table or the sink top as if feeling for the object. Sometimes she would ask, “What’s the time?” even though the big round kitchen clock was just in front of her. And always at these times, the same sharp, suspicious question:

“Has any of you brought oranges into the house?”

We shook our heads silently. Oranges were scarce; we’d only tasted them occasionally. On the market in Angers we might see them sometimes: fat Spanish oranges with their thick dimpled rind; finer-grained blood oranges from the South, cut open to reveal their grazed purple flesh… Our mother always kept away from these stalls, as if the sight of them sickened her. Once, when a friendly woman at the market gave us an orange to share, our mother refused to let us into the house until we had washed, scrubbed under our nails and rubbed our hands with lemon balm and lavender, even then claimed she could smell the orange oil on us-left the windows open for two days until it finally vanished. Of course, the oranges of her bad spells were purely imaginary. The scent heralded her migraines, and within hours she was lying in darkness with a lavender-soaked handkerchief across her face and her pills to hand beside her. The pills, I later learned, were morphine.

She never explained. What information we gleaned was gathered from long observation. When she felt a migraine approaching she simply withdrew to her room without giving any reason, leaving us to our own devices. So it was that we viewed these spells of hers as a kind of holiday-lasting from a couple of hours to a whole day or even two-during which we ran wild. They were wonderful days for us, days that I wished would last forever, swimming in the Loire or catching crayfish in the shallows, exploring the woods, making ourselves sick with cherries or plums or green gooseberries, fighting, sniping at one another with potato rifles and decorating the Standing Stones with the spoils of our adventuring.

The Standing Stones were the remains of an old jetty, long since swept away by the currents. Five stone pillars, one shorter than the rest, protruding from the water. A metal staple stuck out from the side of each, bleeding tears of rust into the rotten stone, where boards had once been fixed. It was on these metal protrusions that we hung our trophies; barbaric garlands of fish heads and flowers, signs lettered in secret codes, magical stones, driftwood sculptures. The last pillar stood well into the deep water at a point where the current was especially strong, and it was here we hid our treasure chest. This was a tin box wrapped in oilcloth and weighted with a piece of chain. The chain was secured to a rope, which in its turn was tied to the pillar we all referred to as the Treasure Stone. To retrieve the treasure it was necessary first to swim to the last pillar-no mean feat-then, holding on to the pillar with one arm, to haul up the sunken chest, detach it and swim with it back to the shore. It was accepted that only Cassis could do this. The “treasure” consisted mainly of things no adult would recognize as being of value. The potato guns. Chewing gum, wrapped in greased paper to make it last. A stick of barley sugar. Three cigarettes. Some coins in a battered purse. Actresses’ photographs (these, like the cigarettes, belonged to Cassis). A few issues of an illustrated magazine specializing in lurid stories.

Sometimes Paul Hourias came with us on what Cassis called our “hunting trips,” though he was never fully initiated into our secrets. I liked Paul. His father, Jean-Marc, sold bait on the Angers road and his mother took in mending to make ends meet. He was an only child of parents old enough to be his grandparents, and much of his time was spent keeping out of their way. He lived as I longed to live; in summer he spent whole nights out in the woods without arousing any concern from his family. He knew where to find mushrooms on the forest floor and to make whistles out of willow twigs. His hands were deft and clever, but he was often awkward and slow in speech, and when adults were near he stuttered. Though he was close to Cassis’s age, he did not go to school, but helped instead on his uncle’s farm, milking the cows and bringing them to and from the pasture. He was patient with me too, more so than Cassis, never making fun of my ignorance or scorning me because I was small. Of course, he’s old now. But I sometimes think that of the four of us, he is the one who has aged the least.

Part Two

Forbidden fruit

1

It was already, in early June, promising to be a hot summer and the Loire was low and surly with quicksand and landslides. There were snakes too, more than usual, flat-headed brown adders that lurked in the cool mud in the shallows. Jeannette Gaudin was bitten by one of these as she paddled one dry afternoon, and they buried her a week later in Saint-Benedict’s churchyard, beneath a little plaster cross and an angel. Beloved Daughter…1934–1942. I was a year older than she was.

Suddenly I felt as if a gulf had opened beneath me, a hot, deep hole like a giant mouth. If Jeannette could die, then so could I. So could anyone. Cassis looked down from the height of his fourteen years in some scorn: “You expect people to die in wartime, stupid. Children too. People die all the time.”

I tried to explain and found that I could not. Soldiers dying – even my own father – that was one thing. Even civilians killed in bombing, though there had been little enough of that in Les Laveuses. But this was different. My nightmares worsened. I spent hours watching the river with my fishing net, catching the evil brown snakes in the shallows, smashing their flat clever heads with a stone and nailing their bodies to the exposed roots at the riverbank. A week of this and there were twenty or more drooping lankly from the roots, and the stink – fishy and oddly sweet, like something bad fermented – was overwhelming. Cassis and Reinette were still at school – they both went to the collège in Angers – and it was Paul who found me with a clothespin on my nose to keep out the stench, doggedly stirring the muddy soup of the verge with my net.

He was wearing shorts and sandals, and held his dog, Malabar, on a leash made of string.

I gave him a look of indifference and turned back to the water. Paul sat down next to me. Malabar flopped onto the path, panting. I ignored them both. At last Paul spoke.

“Wh-what’s wrong?”

I shrugged. “Nothing. I’m just fishing, that’s all.”

Another silence.

“For’s-snakes.” His voice was carefully uninflected.

I nodded, rather defiantly.

“So?”

“So nothing.” He patted Malabar’s head. “You can do what you like.”

A pause that crawled between us like a racing snail.

“I wonder if it hurts,” I said at last.

He considered it for a moment as if he knew what I meant, then shook his head.

“Dunno.”

“They say the poison gets into your blood and makes you go numb. Just like going to sleep.”

He watched me noncommittally, neither agreeing nor disagreeing.

“C–Cassis sez that Jeannette Gaudin musta seen Old Mother,” he said at last. “You know. That’s why the snake b-bit her. Old Mother’s curse.”

I shook my head. Cassis, the avid storyteller and reader of lurid adventure magazines (with titles like The Mummy’s Curse or Barbarian Swarm), was always saying things like that.

“I don’t think Old Mother even exists,” I said defiantly. “I’ve never seen her, anyway. Besides, there’s no such thing as a curse. Everyone knows that.”

Paul looked at me with sad, indignant eyes.

“Course there is,” he said. “And she’s down there all right. M-my dad saw her once, way back before I was born. B-biggest pike you ever saw. Week later, he broke his leg falling off of his b-bike. Even your dad got-”

He broke off, dropping his eyes in sudden confusion.

“Not my dad,” I said sharply. “My dad was killed in battle.”

I had a sudden, vivid picture of him marching, a single link in an endless line that moved relentlessly toward a gaping horizon.

Paul shook his head.

“She’s there,” he said stubbornly. “Right at the deepest point of the Loire. Might be forty years old, maybe fifty. Pikes live a long time, the old uns. She’s black as the mud she lives in. And she’s clever, crazy-clever. She’d take a bird sitting on the water as easy as she’d gulp a piece of bread. My dad sez she’s not a pike at all but a ghost, a murderess, damned to watch the living forever. That’s why she hates us.”

This was a long speech for Paul, and in spite of myself I listened with interest. The river abounded with stories and old wives’ tales, but the story of Old Mother was the most enduring. The giant pike, her lip pierced and bristling with the hooks of anglers who had tried to catch her. In her eye, an evil intelligence. In her belly, a treasure of unknown origin and inestimable worth.

“My dad sez that if anyone was to catch her, she’d hafta give you a wish,” said Paul. “Sez he’d settle for a million francs and a look at that Greta Garbo’s underwear.”

He grinned sheepishly. That’s grownups for you, his smile seemed to say.

I considered this. I told myself I didn’t believe in curses or wishes for free. But the image of the old pike wouldn’t let go.

“If she’s there, we could catch her,” I told him abruptly. “It’s our river. We could.”

It was suddenly clear to me; not only possible, but an obligation. I thought of the dreams that had plagued me ever since Father died; dreams of drowning, of rolling blind in the black surf of the swollen Loire with the clammy feel of dead flesh all around me, of screaming and feeling my scream forced back into my throat, of drowning in myself. Somehow the pike personified all that, and though my thinking was certainly not as analytical as that, something in me was suddenly certain-certain-that if I were to catch Old Mother, something might happen. What it might be I would not articulate even to myself. But something, I thought in mounting, incomprehensible excitement. Something.

Paul looked at me in bewilderment.

“Catch her?” he repeated. “What for?”

“It’s our river,” I said stubbornly. “It shouldn’t be in our river.”

What I wanted to say was that the pike offended me in some secret, visceral way, much more so than the snakes: its slyness, its age, its evil complacency. But I could think of no way to say it. It was a monster.

“‘Sides, you’d never do it,” Paul went on. “I mean, people have tried. Grownup people. With lines and nets an’ all. It bites through the nets. And the lines… it breaks them right snap down the middle. It’s strong, see. Stronger than either of us.”

“Doesn’t have to be,” I insisted. “We could trap it.”

“You’d hafta be bloody clever to trap Old Mother,” said Paul stolidly.

“So?” I was beginning to be angry now, and I faced him with fists and face both clenched in frustration. “So we’ll be clever. Cassis and me and Reinette and you. All four of us. Unless you’re scared.”

“I’m not’s-scared, but it’s im-im-impossible.”

He was stuttering again, as he always did when he felt under pressure.

I looked at him.

“Well, I’ll do it on my own if you won’t help. And I’ll catch the old pike too. You just wait.”

For some reason my eyes were stinging. I wiped them furtively with the heel of my hand. I could see Paul watching me with a curious expression, but he said nothing. Viciously, I poked at the hot shallows with my net.

“‘S only an old fish,” I said. Poke. “I’ll get it and I’ll hang it on the Standing Stones.” Poke. “Right there.” I pointed at the Treasure Stone with my dripping net. “Right there,” I said again in a low voice, spitting on the ground to prove that what I said was true.